Shin bone indentations represent a complex clinical presentation that can stem from various pathological processes affecting the tibia. When patients present with visible or palpable depressions in the anterior tibial surface, healthcare professionals must conduct a systematic evaluation to differentiate between benign anatomical variations and serious underlying conditions. The tibia’s prominent subcutaneous position makes it particularly susceptible to both traumatic injuries and disease processes that can alter its normal contour. Understanding the anatomical framework, recognising pathological patterns, and implementing appropriate diagnostic protocols are essential for accurate assessment and optimal patient outcomes.

Anatomical structure and normal tibial morphology

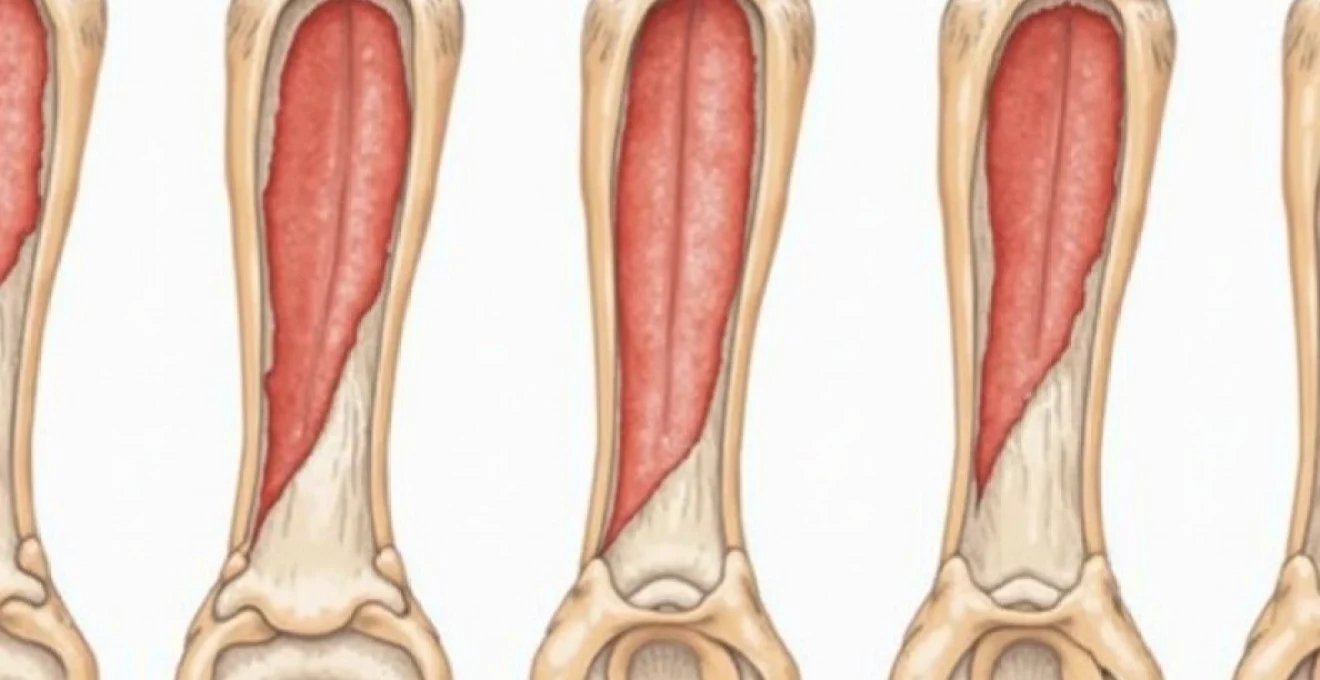

The tibia’s complex architecture forms the foundation for understanding pathological changes that can result in bone indentation. As the larger of the two lower leg bones, the tibia bears significant weight-bearing loads whilst maintaining structural integrity through its sophisticated design. The bone’s triangular cross-section at the shaft level provides optimal strength-to-weight ratios, whilst the prominent anterior border creates the characteristic shin contour visible beneath the skin.

Cortical bone architecture of the anterior tibial shaft

The anterior cortex of the tibial shaft demonstrates remarkable thickness variations along its length, typically measuring between 3-7 millimetres in healthy adults. This cortical density reaches its maximum at the mid-shaft level, where mechanical stresses are greatest during weight-bearing activities. The cortical architecture consists of densely packed osteons arranged predominantly in longitudinal patterns, providing exceptional resistance to bending and torsional forces.

Microscopic examination reveals Haversian systems aligned parallel to the bone’s long axis, creating channels for vascular supply and nerve innervation. The periosteal surface maintains continuous bone remodelling through osteoblast and osteoclast activity, responding dynamically to mechanical loading patterns and metabolic demands.

Medullary canal dimensions and trabecular patterns

The medullary canal occupies the central portion of the tibial shaft, housing bone marrow and providing structural support through its trabecular network. Normal canal dimensions vary significantly between individuals, typically measuring 8-15 millimetres in diameter at the mid-shaft level. Trabecular bone density within the metaphyseal regions demonstrates predictable patterns that change with age and loading conditions.

The trabecular architecture follows stress trajectories, with primary trabeculae aligned along lines of maximum compressive and tensile forces. Secondary trabeculae provide additional structural support whilst creating spaces for hematopoietic tissue and fat storage. This intricate framework maintains bone strength whilst minimising overall weight.

Periosteal surface characteristics and variations

The periosteal surface presents distinct regional variations that influence clinical examination findings. The anterior border typically exhibits a sharp, well-defined contour in healthy individuals, whilst the medial surface demonstrates a smoother, more rounded profile. These anatomical landmarks serve as reference points for identifying abnormal contours or indentations.

Normal periosteal thickness ranges from 0.1-0.3 millimetres, though this measurement increases during periods of active bone formation or repair. The periosteum consists of an outer fibrous layer containing blood vessels and an inner cambium layer responsible for bone formation. Understanding these normal characteristics helps differentiate physiological variations from pathological changes.

Age-related changes in tibial bone density distribution

Bone density distribution undergoes predictable changes throughout life, affecting the tibia’s structural properties and appearance. Peak bone mass typically occurs during the third decade of life, followed by gradual decline at approximately 1-2% annually after age 40. Cortical thinning becomes more pronounced in elderly individuals, potentially creating the appearance of surface irregularities or indentations.

Gender differences significantly influence bone density patterns, with women experiencing more rapid bone loss following menopause due to decreased oestrogen levels. These physiological changes can alter normal tibial contours, making it essential to consider age and gender when evaluating apparent bone indentations.

Pathological causes of shin bone indentation

Pathological processes affecting the tibia can create various types of bone indentations through different mechanisms. Infectious, neoplastic, metabolic, and developmental disorders each produce characteristic patterns of bone destruction or remodelling. Recognition of these patterns enables healthcare professionals to narrow differential diagnoses and guide appropriate investigations. The severity and distribution of indentations often correlate with the underlying pathological process’s extent and chronicity.

Osteomyelitis-induced cortical destruction and sequestrum formation

Acute osteomyelitis represents one of the most serious causes of tibial bone indentation, characterised by rapidly progressive cortical destruction. The infectious process typically begins within the medullary cavity before spreading to involve cortical bone and periosteal tissues. Bacterial enzymes and inflammatory mediators break down bone matrix, creating areas of cortical thinning that can progress to frank perforation.

Sequestrum formation occurs when segments of necrotic bone become separated from viable tissue, creating characteristic radiographic appearances. These sequestra often contribute to chronic infection cycles and delayed healing, requiring surgical intervention for complete resolution. The resulting bone defects can produce permanent indentations even after successful treatment.

Fibrous dysplasia and McCune-Albright syndrome manifestations

Fibrous dysplasia creates characteristic shepherd’s crook deformity patterns in affected bones, though tibial involvement typically produces different manifestations. The condition involves replacement of normal bone and marrow with fibrous tissue containing immature woven bone. This abnormal tissue lacks the structural integrity of normal cortical bone, leading to progressive deformation under mechanical loading.

McCune-Albright syndrome represents the polyostotic form associated with endocrine dysfunction and characteristic skin pigmentation. Tibial lesions in this condition often demonstrate mixed sclerotic and lytic changes, creating irregular surface contours and potential stress fracture sites. The progressive nature of these lesions requires long-term monitoring and potential surgical intervention.

Paget’s disease Flame-Shaped lesions in tibial shaft

Paget’s disease produces distinctive flame-shaped lesions that advance along the tibial shaft with characteristic radiographic appearances. The condition involves abnormal bone remodelling with excessive osteoclast activity followed by disorganised new bone formation. This process creates enlarged, weakened bone with irregular surface contours and potential for pathological fractures.

The advancing edge of Paget’s disease typically demonstrates a V-shaped lucent zone on radiographs, representing active bone destruction. Behind this advancing front, sclerotic changes develop as new bone formation attempts to compensate for the destroyed tissue. These changes can produce significant tibial deformity and surface irregularities.

Osteosarcoma and ewing’s sarcoma bone destruction patterns

Primary bone tumours create various patterns of bone destruction that can result in surface indentations or frank cortical defects. Osteosarcoma typically produces mixed lytic and sclerotic changes with characteristic sunburst spiculation and soft tissue mass formation. The aggressive nature of these tumours often leads to rapid cortical destruction and pathological fractures.

Ewing’s sarcoma demonstrates more subtle early changes, often presenting with permeative bone destruction and layered periosteal reaction. The classic “onion skin” periosteal response may not be apparent in early stages, making diagnosis challenging. Both tumour types require urgent evaluation and multidisciplinary management.

Chronic osteomyelitis brodie’s abscess presentation

Brodie’s abscess represents a chronic form of osteomyelitis characterised by well-circumscribed intraosseous cavities surrounded by sclerotic bone. These lesions typically develop following inadequately treated acute infections or in patients with compromised immune systems. The chronic inflammatory process can weaken surrounding cortical bone, leading to surface depressions or pathological fractures.

The characteristic radiographic appearance includes a central lucent cavity with surrounding sclerosis and minimal periosteal reaction. However, advanced cases may demonstrate cortical thinning or breakthrough, creating palpable surface irregularities. Surgical drainage and antibiotic therapy are often required for definitive management.

Traumatic aetiology and Stress-Related deformities

Traumatic injuries to the tibia can result in various forms of bone indentation through direct impact, repetitive stress loading, or secondary complications from initial injuries. The subcutaneous location of the tibial shaft makes it particularly vulnerable to direct trauma, whilst its weight-bearing function subjects it to repetitive mechanical stresses. Understanding these traumatic mechanisms helps healthcare professionals recognise injury patterns and predict potential complications that may develop following initial treatment.

Chronic compartment syndrome tibial stress reactions

Chronic compartment syndrome creates a cascade of physiological changes that can ultimately affect tibial bone structure and appearance. Elevated intracompartmental pressures reduce blood flow to muscles, fascia, and periosteal tissues, potentially compromising bone nutrition and remodelling processes. Ischaemic conditions can lead to localised bone weakening and altered surface contours over time.

The anterior compartment’s close relationship with the tibial periosteum makes it particularly susceptible to pressure-related changes. Athletes participating in running sports frequently develop this condition, which may progress to stress fractures if left untreated. Early recognition and appropriate management are essential to prevent permanent bone deformities.

Medial tibial stress syndrome periostitis changes

Medial tibial stress syndrome, commonly known as shin splints, involves inflammatory changes along the posteromedial tibial border that can create characteristic bone changes over time. The condition typically results from repetitive traction forces applied by the deep posterior compartment muscles and fascial attachments. Chronic inflammation can stimulate periosteal thickening and irregular bone formation along affected areas.

Advanced cases may demonstrate radiographic changes including cortical irregularities, periosteal thickening, or small stress fractures. These changes can create palpable ridges or depressions along the medial tibial surface. The progression from functional pain to structural changes emphasises the importance of early intervention and activity modification.

Complete and incomplete stress fracture morphology

Stress fractures represent the end stage of repetitive loading that exceeds bone’s adaptive capacity. The tibia ranks among the most commonly affected bones, particularly in military recruits and distance runners. Incomplete stress fractures may present as subtle cortical irregularities or linear lucencies that can be mistaken for surface indentations during clinical examination.

Complete stress fractures create obvious discontinuities in bone structure, often accompanied by callus formation and local deformity. The healing process may result in permanent alterations to normal bone contour, particularly if initial fracture alignment was suboptimal. High-risk locations include the anterior cortex at the junction of the middle and distal thirds, where tensile stresses concentrate.

Post-traumatic osteomyelitis secondary bone loss

Post-traumatic osteomyelitis represents a serious complication of open tibial fractures that can result in significant bone loss and deformity. The combination of initial traumatic damage, surgical interventions, and infectious processes creates complex patterns of bone destruction. Chronic infection often necessitates multiple debridement procedures, leading to segmental bone defects and surface irregularities.

The management of infected nonunions frequently requires staged reconstruction procedures, including temporary antibiotic-impregnated spacers and definitive bone grafting or transport techniques. These interventions can alter normal tibial anatomy, creating permanent changes to bone contour and length. Long-term monitoring is essential to detect potential complications or recurrent infection.

Advanced imaging protocols for tibial indentation assessment

Contemporary imaging techniques provide unprecedented detail for evaluating tibial bone indentations and their underlying causes. The evolution from conventional radiography to advanced cross-sectional imaging has revolutionised diagnostic capabilities, enabling earlier detection of subtle pathological changes and more accurate characterisation of disease extent. Selecting appropriate imaging modalities requires understanding each technique’s strengths and limitations whilst considering patient factors such as age, symptoms, and clinical presentation.

High-resolution CT multiplanar reconstruction techniques

High-resolution computed tomography offers superior cortical bone detail compared to conventional radiography, making it invaluable for assessing tibial surface irregularities. Modern CT scanners achieve spatial resolution of 0.5 millimetres or less, enabling detection of subtle cortical defects or early stress fractures. Multiplanar reconstruction techniques allow comprehensive evaluation from multiple viewing angles, revealing pathological changes that may be obscured on axial images alone.

Advanced post-processing techniques including volume rendering and maximum intensity projections provide three-dimensional perspectives of bone architecture. These reconstructions prove particularly valuable for surgical planning when bone defects require grafting or internal fixation. Quantitative CT measurements can assess bone density and cortical thickness with remarkable precision, supporting both diagnosis and treatment monitoring.

MRI T1-Weighted and STIR sequence interpretation

Magnetic resonance imaging excels at evaluating soft tissue involvement and bone marrow changes associated with tibial indentations. T1-weighted sequences provide excellent anatomical detail and demonstrate bone marrow fat replacement that may accompany various pathological processes. Short tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences offer superior sensitivity for detecting bone marrow oedema and early inflammatory changes.

The ability to assess surrounding soft tissues simultaneously makes MRI invaluable for evaluating potential complications such as abscess formation or tumour extension. Dynamic contrast enhancement can help differentiate between active infection and post-treatment changes, guiding appropriate management decisions. However, motion artefacts and patient claustrophobia can limit image quality in some cases.

Bone scintigraphy Three-Phase uptake patterns

Bone scintigraphy remains valuable for detecting early metabolic bone changes that precede morphological alterations visible on other imaging modalities. The three-phase technique provides information about blood flow, soft tissue uptake, and delayed bone uptake patterns. These patterns can help differentiate between various pathological processes affecting the tibia.

Increased uptake patterns may indicate active bone formation, infection, or neoplastic processes, whilst decreased uptake might suggest avascular changes or certain medications’ effects. The technique’s high sensitivity makes it useful for screening multiple skeletal sites simultaneously, though specificity remains limited compared to other modalities.

Digital radiography enhancement and measurement protocols

Digital radiography continues to serve as the initial imaging modality for most tibial complaints, offering excellent cost-effectiveness and availability. Modern digital systems provide superior contrast resolution compared to conventional film-screen combinations, enabling better visualisation of subtle bone changes. Edge enhancement algorithms can improve cortical definition, making small indentations or irregularities more apparent.

Standardised measurement protocols ensure reproducible assessments of bone alignment, cortical thickness, and deformity angles. Digital archiving systems facilitate comparison with previous examinations, enabling detection of progressive changes over time. Weight-bearing radiographs provide functional information about bone loading patterns that may not be apparent on non-weight-bearing studies.

Differential diagnosis framework and clinical correlation

Establishing an accurate differential diagnosis for tibial bone indentations requires systematic integration of clinical presentation, physical examination findings, and imaging characteristics. The diagnostic process begins with careful history-taking to identify potential risk factors, symptom patterns, and temporal relationships. Physical examination should assess local signs of inflammation, mechanical alignment, and functional limitations whilst considering the patient’s overall health status and activity level.

The key to accurate diagnosis lies in recognising that similar clinical presentations can result from vastly different underlying pathological processes, each requiring distinct treatment approaches.

Age represents a crucial factor in narrowing differential diagnoses, as certain conditions demonstrate characteristic age distributions. Paediatric patients more commonly develop osteomyelitis or developmental abnormalities, whilst elderly individuals are more susceptible to pathological fractures or metastatic disease. Gender differences also influence disease probability, with stress fractures being more common in female athletes due to hormonal and biomechanical factors.

The temporal evolution of symptoms provides valuable diagnostic clues, with acute presentations suggesting traumatic or infectious aetiologies, whilst chronic progressive symptoms may indicate neoplastic or metabolic processes. Pain characteristics, including location, intensity, and aggravating factors, help differentiate between various conditions. Night pain often suggests neoplastic processes, whilst activity-related pain typically indicates mechanical or stress-related problems.

Laboratory investigations complement imaging studies in certain situations, particularly when infection or metabolic bone disease is suspected. Inflammatory markers

such as C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate can help identify active infectious processes, whilst alkaline phosphatase levels may suggest increased bone turnover in conditions like Paget’s disease.

Systematic evaluation of imaging findings requires understanding characteristic patterns associated with different pathological processes. Lytic lesions with irregular margins suggest aggressive processes such as infection or malignancy, whilst well-defined sclerotic changes often indicate chronic or healing conditions. The presence of periosteal reaction provides additional diagnostic information, with laminated patterns suggesting chronic processes and spiculated patterns indicating more aggressive conditions.

Clinical correlation remains essential, as imaging findings must be interpreted within the context of patient presentation and physical examination findings. Asymptomatic imaging abnormalities may represent incidental findings or resolved conditions, whilst symptomatic patients with normal imaging may require additional investigations or alternative diagnostic approaches. The integration of all available information enables healthcare professionals to develop comprehensive management plans tailored to individual patient needs.

Treatment algorithms and surgical intervention criteria

Management of tibial bone indentations requires individualised treatment approaches based on underlying aetiology, symptom severity, and functional impact. Conservative management remains the first-line approach for many conditions, particularly those related to overuse or minor traumatic injuries. However, certain pathological processes require urgent surgical intervention to prevent complications or disease progression.

Non-operative management typically includes activity modification, anti-inflammatory medications, and physical therapy interventions designed to address underlying biomechanical factors. Progressive loading protocols help restore normal bone metabolism whilst avoiding excessive stress that might perpetuate the underlying problem. Patient education regarding warning signs and activity limitations plays a crucial role in preventing symptom recurrence or progression.

Surgical intervention criteria vary significantly depending on the underlying diagnosis but generally include progressive bone destruction, pathological fractures, or failure of conservative management. Infectious processes often require surgical debridement combined with antibiotic therapy, whilst neoplastic conditions may necessitate biopsy, staging, and multidisciplinary oncological management. The timing of surgical intervention can significantly impact outcomes, making early recognition and appropriate referral essential.

Advanced reconstructive techniques may be required for extensive bone defects resulting from infection, trauma, or tumour resection. Bone transport methods using external fixation devices can regenerate significant bone segments, whilst vascularised bone grafts provide options for complex reconstructions. These procedures require specialised expertise and prolonged rehabilitation periods but can restore function in cases where amputation might otherwise be necessary.

Long-term monitoring protocols should be established for patients with chronic conditions or those at risk for disease recurrence. Regular imaging studies, clinical assessments, and functional evaluations help detect early signs of progression or complications. Patient compliance with follow-up recommendations significantly impacts long-term outcomes, emphasising the importance of clear communication and shared decision-making throughout the treatment process.

Successful management of tibial bone indentations requires early recognition, accurate diagnosis, and appropriate treatment selection based on individual patient factors and underlying pathological processes.

The prognosis for patients with tibial bone indentations varies considerably depending on the underlying cause and treatment response. Many stress-related conditions resolve completely with appropriate conservative management, whilst infectious or neoplastic processes may result in permanent structural changes or functional limitations. Early intervention generally provides the best opportunity for optimal outcomes, regardless of the underlying aetiology.

Multidisciplinary care coordination becomes essential for complex cases involving multiple specialists, including orthopaedic surgeons, infectious disease physicians, oncologists, and rehabilitation specialists. Effective communication between team members ensures comprehensive management whilst avoiding duplicated efforts or conflicting treatment recommendations. Patient-centred care approaches that involve patients in treatment decisions and goal-setting improve satisfaction and compliance with recommended interventions.

Prevention strategies focus on addressing modifiable risk factors such as training errors in athletes, optimising bone health through nutrition and exercise, and prompt treatment of acute injuries to prevent chronic complications. Educational programs targeting high-risk populations can help reduce the incidence of preventable tibial injuries and their associated complications. Regular screening in susceptible populations may enable earlier detection and intervention before significant structural damage occurs.