Muscle fasciculations, or involuntary muscle twitches, affect approximately 70% of the population at some point in their lives. While these fleeting contractions are typically harmless, distinguishing between benign fasciculation syndrome and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis becomes crucial when symptoms persist or intensify. Understanding the fundamental differences between these conditions can alleviate anxiety and guide appropriate medical intervention, particularly given that muscle twitching represents one of the most common neurological concerns prompting consultations with specialists.

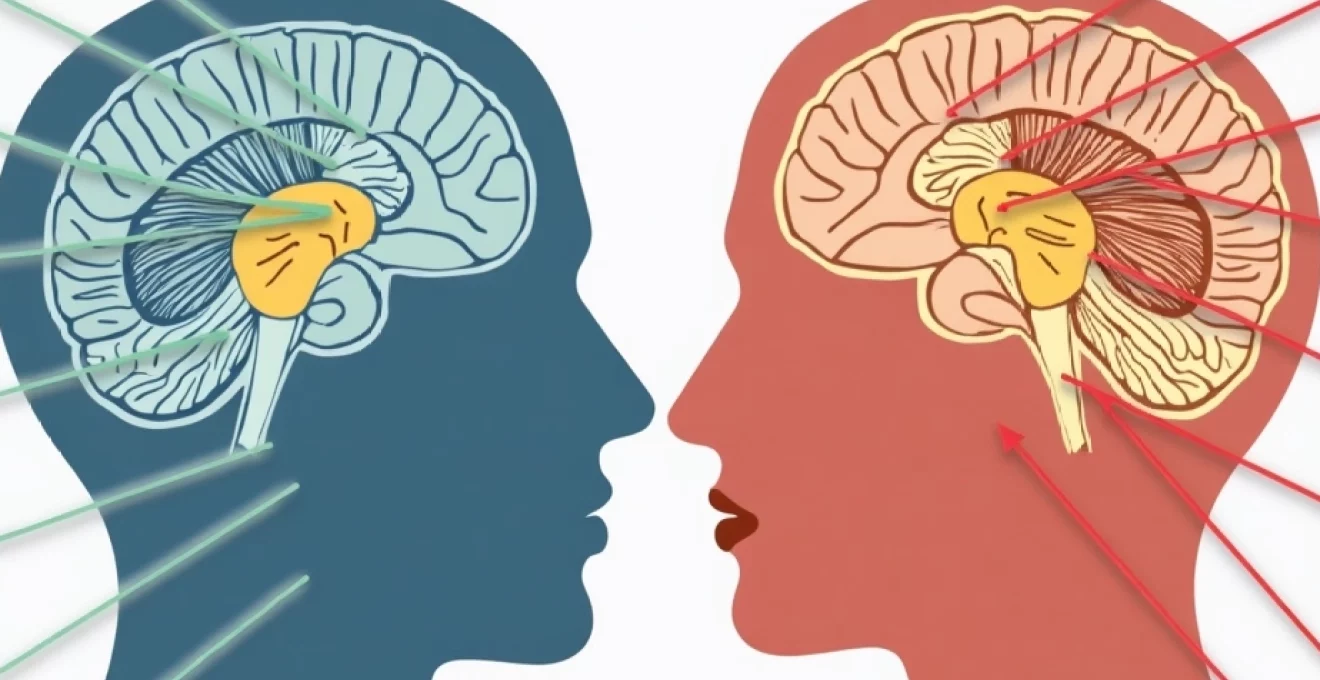

The distinction between benign fasciculation syndrome (BFS) and ALS extends far beyond simple muscle twitching patterns. These conditions represent vastly different pathophysiological processes, with BFS involving temporary nerve hyperexcitability whilst ALS encompasses progressive motor neuron degeneration. Recognising these differences early can prevent unnecessary distress and ensure timely, appropriate medical management.

Clinical presentation and symptomatology: distinguishing fasciculation patterns

The clinical manifestations of benign fasciculation syndrome and ALS present distinct patterns that experienced neurologists can readily differentiate. Understanding these presentations requires examining not only the fasciculations themselves but also their associated symptoms, distribution patterns, and temporal characteristics. The key lies in recognising that whilst both conditions involve muscle twitching, the underlying mechanisms and accompanying features differ substantially.

Benign fasciculation syndrome: widespread muscle twitching without weakness

Benign fasciculation syndrome typically presents as widespread, random muscle twitches that migrate throughout the body without following predictable anatomical patterns. These fasciculations commonly affect the calves, thighs, eyelids, and arms, often occurring when muscles are at rest and diminishing during voluntary movement. Patients frequently describe the twitching as a “popcorn-like” sensation beneath the skin, with individual fasciculations lasting seconds to minutes before spontaneously resolving.

The hallmark characteristic of BFS lies in its benign nature – despite persistent and sometimes bothersome twitching, patients maintain normal muscle strength, coordination, and functional capacity. The absence of progressive weakness distinguishes BFS from more serious motor neuron disorders. Many patients report that stress, caffeine consumption, vigorous exercise, or sleep deprivation can exacerbate their symptoms, whilst relaxation and stress reduction often provide relief.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: progressive motor neuron degeneration manifestations

ALS fasciculations present differently, typically beginning in specific anatomical regions before spreading in a more predictable pattern. Unlike BFS, ALS-related twitching often coincides with progressive muscle weakness, beginning focally and gradually expanding to adjacent muscle groups. The fasciculations in ALS frequently occur in muscles that are simultaneously experiencing weakness and atrophy, creating a distinctive clinical picture of simultaneous upper and lower motor neuron dysfunction.

The progression in ALS follows recognisable patterns, with limb-onset disease typically beginning in the hands, feet, or limbs before spreading centrally. Patients often notice difficulty with fine motor tasks, such as buttoning shirts or writing, alongside the muscle twitching. The combination of fasciculations with progressive weakness, muscle wasting, and hyperreflexia creates the characteristic clinical syndrome that distinguishes ALS from benign conditions.

Cramping patterns and associated sensory symptoms in BFS

Benign fasciculation syndrome frequently includes muscle cramping as a prominent feature, often occurring in conjunction with the fasciculations themselves. These cramps typically affect large muscle groups, particularly in the calves and thighs, and may be more pronounced during periods of increased physical activity or dehydration. The cramping in BFS differs from that seen in metabolic disorders, as it responds well to stretching, hydration, and electrolyte supplementation.

Some patients with BFS report sensory symptoms including tingling, numbness, or a sensation of muscle fatigue without actual weakness. These sensory complaints, whilst concerning to patients, do not indicate nerve damage and typically fluctuate with stress levels and overall health status. The presence of sensory symptoms without objective weakness strongly suggests a benign process rather than motor neuron disease.

Bulbar onset ALS: speech and swallowing dysfunction indicators

Bulbar onset ALS presents unique challenges in differential diagnosis, as fasciculations may occur in facial, tongue, and throat muscles alongside progressive dysfunction of speech and swallowing mechanisms. Patients typically notice slurred speech, difficulty managing saliva, or problems with chewing and swallowing liquids or solids. These symptoms progress relentlessly, unlike the fluctuating nature of benign fasciculations in similar muscle groups.

The fasciculations in bulbar ALS often accompany visible tongue atrophy and weakness, creating a characteristic appearance of a shrunken, rippling tongue surface. This combination of bulbar fasciculations with progressive functional decline represents a medical emergency requiring immediate neurological evaluation. The distinction becomes particularly important as bulbar onset ALS typically progresses more rapidly than limb onset variants.

Electromyography and nerve conduction studies: diagnostic neurophysiological markers

Electrophysiological studies represent the cornerstone of differentiating benign fasciculation syndrome from ALS, providing objective evidence of nerve and muscle function that extends beyond clinical observation. These sophisticated diagnostic tools can detect subtle changes in motor unit morphology, nerve conduction patterns, and muscle membrane stability that may not be apparent during routine clinical examination. The interpretation of these studies requires considerable expertise, as the findings must be correlated with clinical presentation to establish accurate diagnoses.

EMG findings in benign fasciculation syndrome: normal motor unit morphology

Electromyography in patients with benign fasciculation syndrome typically reveals fasciculation potentials without evidence of denervation or reinnervation. The motor unit action potentials maintain normal morphology, duration, and recruitment patterns, indicating intact motor neuron function despite the presence of spontaneous activity. This finding provides crucial reassurance that the underlying motor neurons remain healthy and functional.

The fasciculations detected on EMG in BFS appear as simple, brief potentials that fire irregularly and do not cluster in specific anatomical distributions. The absence of fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves, or abnormal motor unit morphology distinguishes BFS from pathological processes affecting motor neurons. Nerve conduction studies in BFS patients typically show normal conduction velocities, amplitudes, and distal latencies, further supporting the benign nature of the condition.

ALS electrophysiological signatures: denervation and reinnervation changes

ALS produces characteristic EMG changes that reflect the ongoing process of motor neuron death and attempted reinnervation by surviving neurons. The electrophysiological findings include enlarged, polyphasic motor unit action potentials with increased duration and amplitude, indicating reinnervation by surviving motor neurons attempting to compensate for lost units. These changes often precede clinically apparent weakness, making EMG a sensitive tool for early ALS detection.

The pattern of abnormalities in ALS typically affects multiple nerve root levels and bilateral limbs, satisfying established diagnostic criteria for motor neuron disease. The presence of active denervation alongside chronic reinnervation changes creates the pathognomonic electrophysiological signature of ALS. Serial EMG studies often demonstrate progression of abnormalities over time, contrasting sharply with the stable findings typically seen in BFS.

Fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves in motor neuron disease

The presence of fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves represents active denervation and serves as a key differentiating feature between ALS and benign fasciculations. These spontaneous potentials arise from individual muscle fibres that have lost their nerve supply, creating characteristic high-frequency discharges that appear on EMG as sharp, biphasic or triphasic potentials. Their presence indicates ongoing motor neuron death and distinguishes pathological from physiological muscle activity.

In ALS, fibrillation potentials and positive sharp waves appear in specific patterns corresponding to the anatomical distribution of affected motor neurons. The combination of fasciculations with active denervation potentials creates a distinctive electrophysiological profile that strongly suggests motor neuron disease. The absence of these denervation markers in BFS provides important prognostic information and helps guide patient counselling regarding the benign nature of their condition.

Compound muscle action potential amplitude reduction in ALS progression

Nerve conduction studies in ALS demonstrate progressive reduction in compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitudes, reflecting loss of functional motor units over time. This reduction typically occurs without significant changes in conduction velocity, distinguishing ALS from primary demyelinating neuropathies. The pattern of CMAP amplitude loss often correlates with clinical weakness and provides objective measures of disease progression.

Serial nerve conduction studies can track the rate of motor unit loss, providing valuable prognostic information and helping monitor treatment responses. The preservation of normal CMAP amplitudes in BFS patients provides additional evidence of the benign nature of their fasciculations. This objective measure complements clinical assessment and helps differentiate between conditions that might otherwise appear similar based solely on symptomatology.

Muscle biopsy histopathology and laboratory biomarkers

Muscle biopsy rarely becomes necessary for differentiating benign fasciculation syndrome from ALS, as clinical and electrophysiological features typically provide sufficient diagnostic clarity. However, when performed, muscle histopathology reveals distinct patterns that can support or refute suspected diagnoses. In BFS, muscle architecture remains largely normal, with occasional type II fibre atrophy reflecting disuse rather than denervation. The absence of neurogenic changes, target fibres, or grouped atrophy helps confirm the benign nature of the fasciculations.

ALS muscle biopsies demonstrate characteristic neurogenic changes including grouped atrophy, target fibres, and fibre type grouping consistent with denervation and reinnervation cycles. These changes reflect the underlying motor neuron pathology and provide histological confirmation of the clinical diagnosis. Modern biomarker research has identified several promising candidates for ALS diagnosis and monitoring, including neurofilament light chain levels and specific microRNAs. These biomarkers may eventually supplement traditional diagnostic approaches, particularly in cases where clinical presentation remains ambiguous.

Laboratory investigations in both conditions typically focus on excluding mimicking disorders rather than confirming specific diagnoses. Thyroid function tests, vitamin B12 levels, magnesium, and calcium concentrations help identify treatable causes of muscle fasciculations. Creatine kinase levels usually remain normal in both BFS and early ALS, though may become elevated in advanced ALS due to muscle breakdown. The development of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for ALS represents an active area of research that may improve diagnostic accuracy in challenging cases.

Disease progression trajectories and prognotic indicators

The fundamental difference in disease trajectory between benign fasciculation syndrome and ALS cannot be overstated. BFS follows a stable or fluctuating course without progressive deterioration, whilst ALS demonstrates relentless progression despite therapeutic interventions. Understanding these different trajectories helps clinicians provide appropriate prognostic counselling and guides treatment planning. Patients with BFS may experience symptom fluctuations related to stress, fatigue, or lifestyle factors, but do not develop progressive weakness or functional decline.

ALS progression follows variable patterns depending on phenotype, with survival ranging from months to decades in rare cases. The rate of functional decline, measured by scales such as the ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R), provides important prognostic information and helps guide care planning. Bulbar onset ALS typically progresses more rapidly than limb onset disease, with median survival times of 2-3 years compared to 3-5 years respectively. The identification of specific genetic mutations, such as SOD1 or C9orf72 expansions, can provide additional prognostic information in familial cases.

Recent research has identified several factors that influence ALS progression rates, including age at onset, site of symptom initiation, and specific genetic variants. Younger patients often experience slower progression, whilst respiratory onset or rapid spread to bulbar muscles indicates more aggressive disease courses. The development of prognostic models incorporating clinical, genetic, and biomarker data represents an important advance in personalised ALS care. These models help patients and families make informed decisions about treatment options and care planning whilst providing realistic expectations about disease trajectory.

The ability to accurately predict disease progression in ALS has transformed patient counselling and clinical trial design, allowing for more targeted interventions and realistic goal setting.

Differential diagnosis: kennedy’s disease, spinal muscular atrophy, and multifocal motor neuropathy

Several conditions can mimic aspects of both benign fasciculation syndrome and ALS, requiring careful consideration during diagnostic evaluation. Kennedy’s disease (X-linked spinobulbomuscular atrophy) presents with fasciculations, weakness, and bulbar symptoms similar to ALS but follows a more indolent course with additional features including gynaecomastia and diabetes mellitus. Genetic testing for CAG repeat expansions in the androgen receptor gene provides definitive diagnosis and helps distinguish this condition from ALS in appropriate clinical contexts.

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in adults can present with fasciculations and weakness patterns that overlap with ALS, particularly in cases with predominant lower motor neuron involvement. However, SMA typically demonstrates a more symmetrical weakness pattern without upper motor neuron signs, and genetic testing can identify deletions or mutations in the SMN1 gene. The distinction becomes particularly important given the availability of specific treatments for SMA that differ markedly from ALS management strategies.

Multifocal motor neuropathy (MMN) represents another important differential diagnosis, presenting with asymmetric weakness and fasciculations that may mimic ALS. However, MMN typically affects distal muscles preferentially, demonstrates conduction blocks on nerve conduction studies, and responds to immunomodulatory treatments. The presence of anti-GM1 ganglioside antibodies supports the diagnosis in appropriate clinical settings, though these antibodies are not universally present in MMN patients.

Distinguishing between these motor neuron disorders requires integration of clinical presentation, electrophysiological findings, and targeted genetic or immunological testing to ensure accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment selection.

Treatment protocols and management strategies for each condition

Management approaches for benign fasciculation syndrome focus primarily on symptom relief and patient reassurance, as the condition carries an excellent prognosis without risk of progression to serious neurological disease. Initial treatment typically involves lifestyle modifications including stress reduction techniques, regular exercise, adequate sleep hygiene, and limitation of caffeine intake. Many patients find that identifying and avoiding personal triggers significantly reduces fasciculation frequency and intensity.

When lifestyle modifications prove insufficient, pharmacological interventions for BFS may include magnesium supplementation, anticonvulsants such as gabapentin or carbamazepine, or muscle relaxants like baclofen. The key principle in BFS management involves reassurance and education about the benign nature of the condition, as anxiety about symptoms often perpetuates the fasciculation cycle. Regular follow-up appointments help monitor symptom stability and provide ongoing reassurance to patients concerned about disease progression.

ALS management requires a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach involving neurologists, respiratory therapists, nutritionists, speech pathologists, and palliative care specialists. Current treatments focus on slowing disease progression with medications like riluzole and edaravone, whilst symptomatic management addresses issues including muscle cramps, excessive salivation, respiratory insufficiency, and nutritional maintenance. The timing of interventions such as gastrostomy tube placement and non-invasive ventilation requires careful coordination to maintain quality of life whilst preventing complications.

Recent advances in ALS treatment include the approval of new medications targeting specific genetic variants, such as tofersen for SOD1-related ALS, representing a shift towards personalised medicine approaches. Clinical trials continue to evaluate novel therapeutic strategies including stem cell therapies, antisense oligonucleotides, and combination treatment protocols. The establishment of specialised ALS clinics has improved outcomes by providing coordinated care and ensuring timely implementation of supportive interventions. Patient and family education about disease progression, treatment options, and advance care planning represents an essential component of comprehensive ALS management that extends beyond purely medical interventions.

The contrast between BFS and ALS management strategies reflects the fundamental difference in disease prognosis, with BFS requiring primarily reassurance and lifestyle modifications whilst ALS demands aggressive multidisciplinary intervention to optimise quality of life and functional preservation.